Wendy Vogel and Kinke Kooi in conversation upon the occasion of Kooi’s solo exhibition The Grotesk of Raising on view at Adams and Ollman August 7 through September 11

Wendy Vogel: Can you tell me about the work that I see behind you?

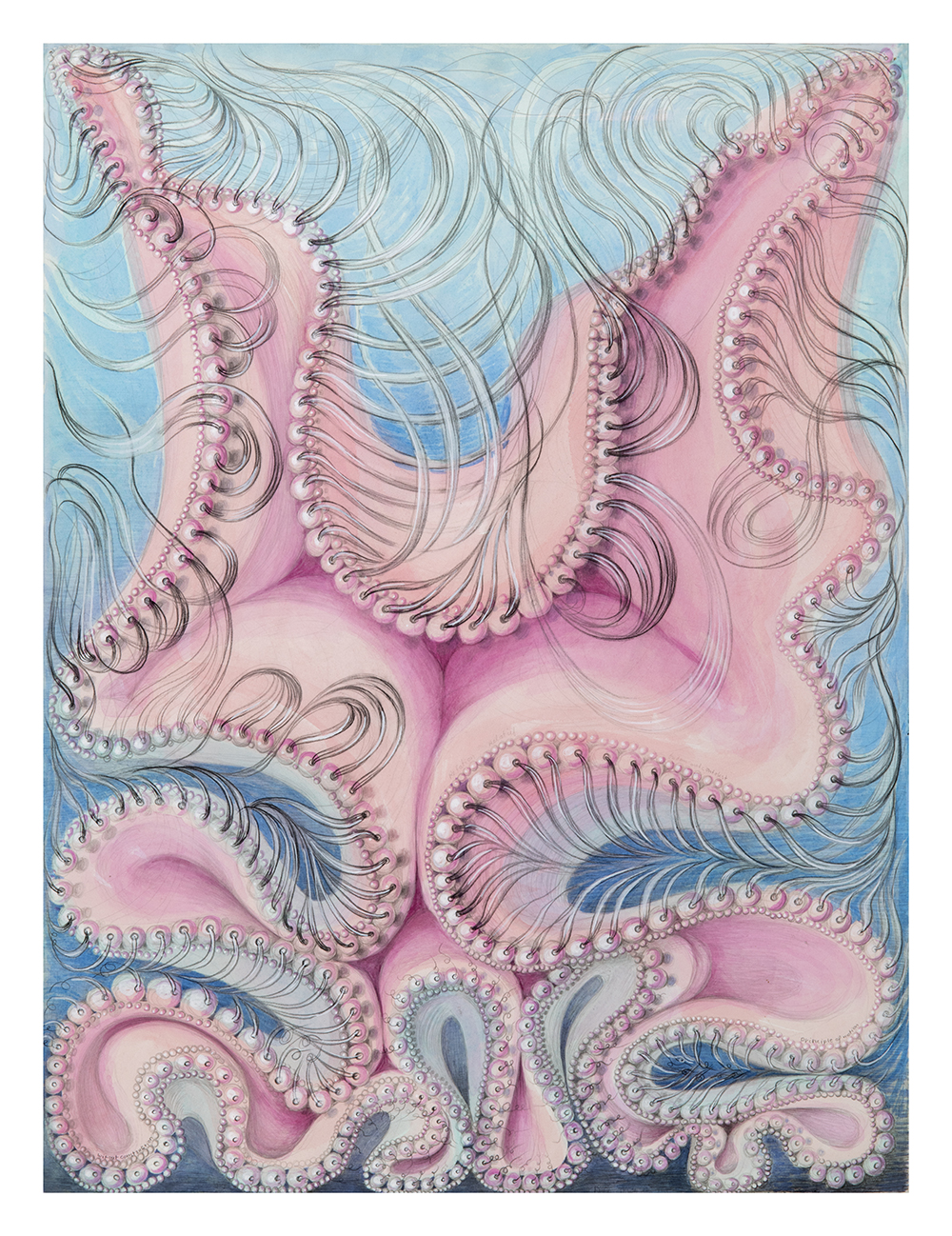

Kinke Kooi: Yes, this big one is a triptych, The Grotesk of Raising (2021). The middle panel shows the mother plant that grows her branches out of shape into the outer panels, into a new reality. I squeeze my work into the shape of the paper so it always fits. I consider a household as a fitting form as well. The mother plant is mostly considered the plant for cuttings. One can see the branches as children, like creepers that grow roots on any place and settle on new and different grounds, a life on their own. At that point you can cut off the branches without it dying. The spaces between the separate parts of the triptych are about that: holding and letting go.

Kinke Kooi, The Grotesk of Raising (2021)

I heard a story once about a dog that was very afraid in new situations. His owner bought him a little vest that you could belt very tight, in order to support him and take away his fear.

WV: They call that a thunder vest in the U.S.

KK: Exactly! I once read an interview with a woman, Temple Grandin, who developed a machine that could hold her in a supportive and pressing grip, so that she could relax. To swaddle her, as it were.

WV: I bought a weighted blanket for anxiety relief, which is not that heavy — it’s about 6 kg.

KK: In the old days we had blankets made of kapok that were really heavy. I loved to sleep under these blankets. I think people knew you needed some weight on yourself, in order not to vaporize into thin air.

“I pay attention to shapes I feel sympathy for and I’ll start to draw them.”

—Kinke Kooi

WV: I read that sometimes you work on an individual piece for up to a year. Can you talk more about your process? Do you work on many pieces at the same time, or is the process sequential?

KK: Yes, I mostly work on one piece at a time, sometimes even up to a year (usually about three months), so my way of working is very inefficient. I think for a while about which subjects fascinate me. I pay attention to shapes I feel sympathy for and I'll start to draw them. But then I felt that drawing the background was very difficult for me. I promised myself to make the process easy, so I thought, I’ll stuff it with bulges, drawn in endless repetitive lines. Later on I realized that, in this way, the background became a supportive system. These days my bulges turned outside in, into folds.

Kinke Kooi, Principle of Motion, 2016

One of my favorite subjects are shawls, with their beautifully decorated edges ending in fringes like hair; I love their movability and pliability, like in Flamenco dancing. But I wondered how to draw it: will it not be considered too feminine and too superficial? Funny how these two words slip into my mind so easily together: When I feel ashamed of something it turns out to always be a political issue. When I made the drawing I called it Principle of Motion (2016); it looks like a scarf, but it could be tissue or flesh as well. I found out it’s a holistic system, if you don’t cut off the edges. I have this opposition to sharpness, and a soft scarf without an end is describing a whole. If you want a shape to look sharp you have to cut off the unnecessary...

I find out through drawing. That’s the process. I promised myself to always work as long as I wanted, because at the academy they always told me to stop at a certain point, which took away the joy. It’s like eating a plate of nice food and someone pulls it away and tells you, “You’ve had enough!” Then you keep thinking about the plate all the time. I keep drawing until the moment I’m satisfied. That can last a long time, but I love the details. In this work you can see a wood louse, ants, a little broom — that’s the symbol of the witches. I have elements, little symbols, I want to repeat in the drawing in the same way. I don’t always have to invent something new, because I want to feel secure. My work is very much about support and security.

WV: I see some collage works in the studio. Is that a newer practice for you?

KK: No, I’ve done collage for a long time. I started with Q-Tips. I saw these Q-Tips, and at the time I thought they were so sexy and beautiful, and they were also trying to enter the body.

One of my rules as an artist is that I can do everything I want. If I don’t feel like drawing something, I can sew it on. That’s why I started to paint auras on photographs as well — auras around animals, objects, beloved people and pubic hair — because I didn’t feel like drawing the whole body and all of these subjects.

It is, in a way, very difficult to do exactly what you want, because you have to set aside your expectations. You have to make big decisions to leave behind what you don’t like to do anymore.

It’s also a break in style. Another artist saw one of my collages and said, “Oh, but that’s a break in style!” That interested me. What is a break of style? Why do you have to stay with your style? You can break out of style.

“In a way I think we are still starving for these kinds of images.”

—Kinke Kooi

WV: Even with breaks in your style and technique, there is a continuity in your overarching project as an artist. There’s a quote that you gave in an interview with the gallerist Hudson in 2013: “After I had my daughter I became more interested than ever in the images that she would see in her lifetime. I was shocked by how one-dimensional images of women still are in our culture. I call that visual loneliness. I think femininity still deserves and needs to be visualized from more perspectives. I would like to fill in these gaps in our visual information.” Over the last few decades, there’s been a proliferation of feminine imagery in popular culture and fine art. Do you still consider the terms of your work in the same way?

Kinke Kooi, Cellulitis, 1992

KK: Our daughter is 31 now. I think that everything that is out of the norm is still considered grotesque, even in this proliferation. When our daughter was born I started to draw my own butt, which I thought was way out of proportion (Cellulitis, 1992), just in order to visualize it. And also, when I draw something I start to love it. That gaze of really looking at something is so beautiful and healing! These days, like you say, big things are happening, so important and wonderful. And yet I think our culture is only beginning to explore the inclusive gaze. My interest has shifted more towards shapes of hospitality: to be very open and welcoming is often approached in a suspicious way; there is a fine line between hospitality and the hostess. In a way I think we are still starving for these kinds of images.

WV: I’d also like to hear your perspective on figuration, which has swung in and out of favor over the last few decades. As someone who has been making work that is erotic, biological, yet also crosses into the realm of fantasy and symbolism, how have you seen the reception of your work change over that time?

KK: Art has many hidden rules about what you should or should not do. The artist in me forces its taste upon me. Often I’m ashamed of it and I have to figure out why. Figurative means the figure, it’s the body. It’s very Christian to dislike the body, the flesh and especially women’s bodies, because they’re associated with sin and weakness.

In the ‘90s bone-naked was the word. But what is bone-naked? It’s a skeleton without any flesh. So I thought, I’ll draw the flesh. I like skin; I like tissue; I like scarves; I like fabrics; I like climbers. And what do they not have? Bones. They are boneless. I make boneless work. And because the unspoken dictate of good taste prohibited it, it was not done.

Every shape has a philosophy. And by drawing it I learn to understand what it means. I think it’s very interesting to discover the time by its shapes.

WV: Clams and mollusks are key motifs in the new work. Oysters make pearls as a defense mechanism, when there’s an intrusive element in their shells. Did you gravitate toward this theme during the COVID-19 lockdown period?

KK: That is the beauty of the pearl: it prevents the sharp from being sharp. I go back and forth over time with topics. In my last show with Hudson (Feature Inc., 2013) I had clamshells as well. I read somewhere that Mary was the clam and Jesus was the pearl. I realize the clam is the holder, is the flesh, and in a way it could be the womb. The womb is so ignored in art, but why? It could be a philosophy as well. (Concept and conception are etymologically the same!). And that’s what I mean with scarves too: it’s being around. We all started out in the womb. I learned the term, in English, of “fleshing it out.” It’s a beautiful phrase; flesh is around the bones. So, I want to get my head around what is being around. There is a smothering element as well. Sometimes it needs to be tight, and sometimes it’s too tight. There again is a fine line between bonding and bondage. And in relation, Einstein’s theory of relativity, it means you are defined as something in combination with something else.

WV: I want to return to the idea of bone-nakedness. Is that one word, bone-naked?

KK: I heard an artist use it, but we use it in Holland as well. We say “cut off to the bone.” It means the complete truth. I think it’s very post-religious. We are still in a post-religious period, whether you are raised religious or not. Our religion thinks flesh is for the women and bone-nakedness is for the men, because they are honest and stable and unchangeable. Women do change. That’s why we talk about the grotesque. If you’re pregnant, you change your body, and in America I hear girls calling themselves fat. It’s not true; you’re pregnant. And if you look at Mary in religion, in a way they all have the same body. It’s like something to put your clothes on. It’s like nothing, no real shape.

WV: It’s all fabric, the depiction of saints and religious figures.

KK: Amorphousness and formlessness were scarier when I was young. I love the way these shapes are reappearing in the arts these days: I think that is very beautiful. It seems to me that young people are very much in touch with it.

WV: Do you live close to the sea?

KK: No, I was raised close to the sea, just behind the dikes. I live now in nature, with waterfalls. Why do you ask?

“It is because there’s so much about women that is unknown, as unknown as the deep sea. And where do some men want to go now with their rockets? To Mars!”

WV: I wondered if you spent time at the sea swimming and observing clams, mollusks, other sea creatures. The work is very much about the interior of the body, but I think of a bodily interior as an analog to underwater landscapes. There’s a history of equating the female body with the sea as two types of unfamiliar territories, as well as a sublime fear of the sea’s depths.

KK: Exactly. And Mary means mare, the sea. I had a whole series of works called “Under the Surface.” It is because there’s so much about women that is unknown, as unknown as the deep sea. And where do some men want to go now with their rockets? To Mars! In order to survive there, they will have to live in caves, a metaphor for the womb; very funny, I think...

But also, the aesthetic of the deep sea is very much like jewelry. It is boneless, way more like scarves and fabrics waving and moving. It’s very important to me.

WV: Hearing you talk about your attraction to dance and the movement of fabric, I wonder if you have a movement practice? Do you make clothes?

KK: I’m really tall and big, and my coordination and sense of rhythm are not very good. But I love to look at dance! And I loved to dance in discos when I was young. It’s just that my body is not very danceable.

But I have a very special mother, who dresses like it’s her own art form — many necklaces, scarves and clothes. As a child I always loved looking at her. She is so beautiful! We lived on a farm and she was completely different from everybody. I got a lot of support from her. She is very free and really wild and shameless. I think I identified myself with her a lot. She’s my hero. She didn’t come from such a background, though; she invented it herself. That was very inspirational to me, that you can invent your own life.

WV: I’m part of an online platform for writers, and someone recently posted a series of prompts based on the work of the poet Ross Gay. One of them asked: What’s the difference between pleasure and joy? I’d like to ask you the same question, and how that might play out in your work.

KK: My native language is different so I don’t know the nuances well, but I love the words pleasure and joy. I would choose the word joy. We have a word in Holland called zin, which means “that you feel like it,” as in, “I feel like eating a cookie.” But, similar to your word 'sense', 'zin' can also mean 'meaning' in a different context; and that makes it tricky. A Dutch philosopher talked about my work and the notion of lust. And I thought, I don’t want lust! Lust means that there’s only one party involved. If you do something with someone else, it should be both parties who like it. I think that’s zinnelijk. I think joy is better. As for pleasure, I love to do someone a pleasure, but maybe there’s force or expectation in it.

WV: Over the years you’ve discussed your gender presentation — or rather, your relationship to femininity — shifting over time. In the ‘90s, the queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick wrote that one’s gender-y-ness, how much you feel your embodiment of gender, is in constant flux throughout our lives.

KK: As a child I lived on a farm. For a while I tried to walk very boyishly. We had to ride horses, and I was always very afraid. Then I became a woman. I got breasts, and I grew really tall and strong. I was so afraid I was too big and not attractive. I started behaving very femininely, but it was an act as well. In a way my femininity never felt very real, but on the other hand I became very good at it and enjoyed it. This idea in feminism that you have to “act like a man” should not be the standard. Why should we behave like men? I think men should also behave like women: it should be an equal cross-over. When I got pregnant I changed and felt really feminine. Then I entered menopause and I became more male again. I got angrier quicker. All quite exciting.

Similar to our discussion about dance and movement, why can’t we enjoy changes in our hormones over the course of our lives?

![]()

Kinke Kooi, Why Do Men Have Nipples?, 2020

I made a piece called Why Do Men Have Nipples? Nobody taught me these biological lessons. Just by looking one could draw this conclusion: we are the same, like a basic soup, and then you pour some ingredients in. There’s a gradient. My husband airbrushes rainbow gradients into his paintings. Somebody said they were too pleasing and I wondered why? I feel completely attracted to the gradient. I love gradients, one thing bleeding into another. I think that’s the beauty of life.

Wendy Vogel is a writer and critic living in New York. She is a 2018 recipient of a Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Arts Writers Grant in Short Form Writing.

KK: Art has many hidden rules about what you should or should not do. The artist in me forces its taste upon me. Often I’m ashamed of it and I have to figure out why. Figurative means the figure, it’s the body. It’s very Christian to dislike the body, the flesh and especially women’s bodies, because they’re associated with sin and weakness.

In the ‘90s bone-naked was the word. But what is bone-naked? It’s a skeleton without any flesh. So I thought, I’ll draw the flesh. I like skin; I like tissue; I like scarves; I like fabrics; I like climbers. And what do they not have? Bones. They are boneless. I make boneless work. And because the unspoken dictate of good taste prohibited it, it was not done.

Every shape has a philosophy. And by drawing it I learn to understand what it means. I think it’s very interesting to discover the time by its shapes.

WV: Clams and mollusks are key motifs in the new work. Oysters make pearls as a defense mechanism, when there’s an intrusive element in their shells. Did you gravitate toward this theme during the COVID-19 lockdown period?

KK: That is the beauty of the pearl: it prevents the sharp from being sharp. I go back and forth over time with topics. In my last show with Hudson (Feature Inc., 2013) I had clamshells as well. I read somewhere that Mary was the clam and Jesus was the pearl. I realize the clam is the holder, is the flesh, and in a way it could be the womb. The womb is so ignored in art, but why? It could be a philosophy as well. (Concept and conception are etymologically the same!). And that’s what I mean with scarves too: it’s being around. We all started out in the womb. I learned the term, in English, of “fleshing it out.” It’s a beautiful phrase; flesh is around the bones. So, I want to get my head around what is being around. There is a smothering element as well. Sometimes it needs to be tight, and sometimes it’s too tight. There again is a fine line between bonding and bondage. And in relation, Einstein’s theory of relativity, it means you are defined as something in combination with something else.

WV: I want to return to the idea of bone-nakedness. Is that one word, bone-naked?

KK: I heard an artist use it, but we use it in Holland as well. We say “cut off to the bone.” It means the complete truth. I think it’s very post-religious. We are still in a post-religious period, whether you are raised religious or not. Our religion thinks flesh is for the women and bone-nakedness is for the men, because they are honest and stable and unchangeable. Women do change. That’s why we talk about the grotesque. If you’re pregnant, you change your body, and in America I hear girls calling themselves fat. It’s not true; you’re pregnant. And if you look at Mary in religion, in a way they all have the same body. It’s like something to put your clothes on. It’s like nothing, no real shape.

WV: It’s all fabric, the depiction of saints and religious figures.

KK: Amorphousness and formlessness were scarier when I was young. I love the way these shapes are reappearing in the arts these days: I think that is very beautiful. It seems to me that young people are very much in touch with it.

WV: Do you live close to the sea?

KK: No, I was raised close to the sea, just behind the dikes. I live now in nature, with waterfalls. Why do you ask?

“It is because there’s so much about women that is unknown, as unknown as the deep sea. And where do some men want to go now with their rockets? To Mars!”

—Kinke Kooi

WV: I wondered if you spent time at the sea swimming and observing clams, mollusks, other sea creatures. The work is very much about the interior of the body, but I think of a bodily interior as an analog to underwater landscapes. There’s a history of equating the female body with the sea as two types of unfamiliar territories, as well as a sublime fear of the sea’s depths.

KK: Exactly. And Mary means mare, the sea. I had a whole series of works called “Under the Surface.” It is because there’s so much about women that is unknown, as unknown as the deep sea. And where do some men want to go now with their rockets? To Mars! In order to survive there, they will have to live in caves, a metaphor for the womb; very funny, I think...

But also, the aesthetic of the deep sea is very much like jewelry. It is boneless, way more like scarves and fabrics waving and moving. It’s very important to me.

WV: Hearing you talk about your attraction to dance and the movement of fabric, I wonder if you have a movement practice? Do you make clothes?

KK: I’m really tall and big, and my coordination and sense of rhythm are not very good. But I love to look at dance! And I loved to dance in discos when I was young. It’s just that my body is not very danceable.

But I have a very special mother, who dresses like it’s her own art form — many necklaces, scarves and clothes. As a child I always loved looking at her. She is so beautiful! We lived on a farm and she was completely different from everybody. I got a lot of support from her. She is very free and really wild and shameless. I think I identified myself with her a lot. She’s my hero. She didn’t come from such a background, though; she invented it herself. That was very inspirational to me, that you can invent your own life.

WV: I’m part of an online platform for writers, and someone recently posted a series of prompts based on the work of the poet Ross Gay. One of them asked: What’s the difference between pleasure and joy? I’d like to ask you the same question, and how that might play out in your work.

KK: My native language is different so I don’t know the nuances well, but I love the words pleasure and joy. I would choose the word joy. We have a word in Holland called zin, which means “that you feel like it,” as in, “I feel like eating a cookie.” But, similar to your word 'sense', 'zin' can also mean 'meaning' in a different context; and that makes it tricky. A Dutch philosopher talked about my work and the notion of lust. And I thought, I don’t want lust! Lust means that there’s only one party involved. If you do something with someone else, it should be both parties who like it. I think that’s zinnelijk. I think joy is better. As for pleasure, I love to do someone a pleasure, but maybe there’s force or expectation in it.

WV: Over the years you’ve discussed your gender presentation — or rather, your relationship to femininity — shifting over time. In the ‘90s, the queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick wrote that one’s gender-y-ness, how much you feel your embodiment of gender, is in constant flux throughout our lives.

KK: As a child I lived on a farm. For a while I tried to walk very boyishly. We had to ride horses, and I was always very afraid. Then I became a woman. I got breasts, and I grew really tall and strong. I was so afraid I was too big and not attractive. I started behaving very femininely, but it was an act as well. In a way my femininity never felt very real, but on the other hand I became very good at it and enjoyed it. This idea in feminism that you have to “act like a man” should not be the standard. Why should we behave like men? I think men should also behave like women: it should be an equal cross-over. When I got pregnant I changed and felt really feminine. Then I entered menopause and I became more male again. I got angrier quicker. All quite exciting.

Similar to our discussion about dance and movement, why can’t we enjoy changes in our hormones over the course of our lives?

Kinke Kooi, Why Do Men Have Nipples?, 2020

I made a piece called Why Do Men Have Nipples? Nobody taught me these biological lessons. Just by looking one could draw this conclusion: we are the same, like a basic soup, and then you pour some ingredients in. There’s a gradient. My husband airbrushes rainbow gradients into his paintings. Somebody said they were too pleasing and I wondered why? I feel completely attracted to the gradient. I love gradients, one thing bleeding into another. I think that’s the beauty of life.

Wendy Vogel is a writer and critic living in New York. She is a 2018 recipient of a Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Arts Writers Grant in Short Form Writing.